Apple is not just a company; it’s a vision that continues to change the way people interact with one another.

From now on, May 26 really ought to be dubbed 'International Branding and Design Day'. Why? Because in 2010, on this day, one man's unshakeable vision of business as art form was vindicated. This was the day Apple's market value hit $229 billion – the day it supplanted long-time rival Microsoft as the world's largest and most important tech company.

But Apple is not just a company; it's a vision that continues to change the way people interact with one another.

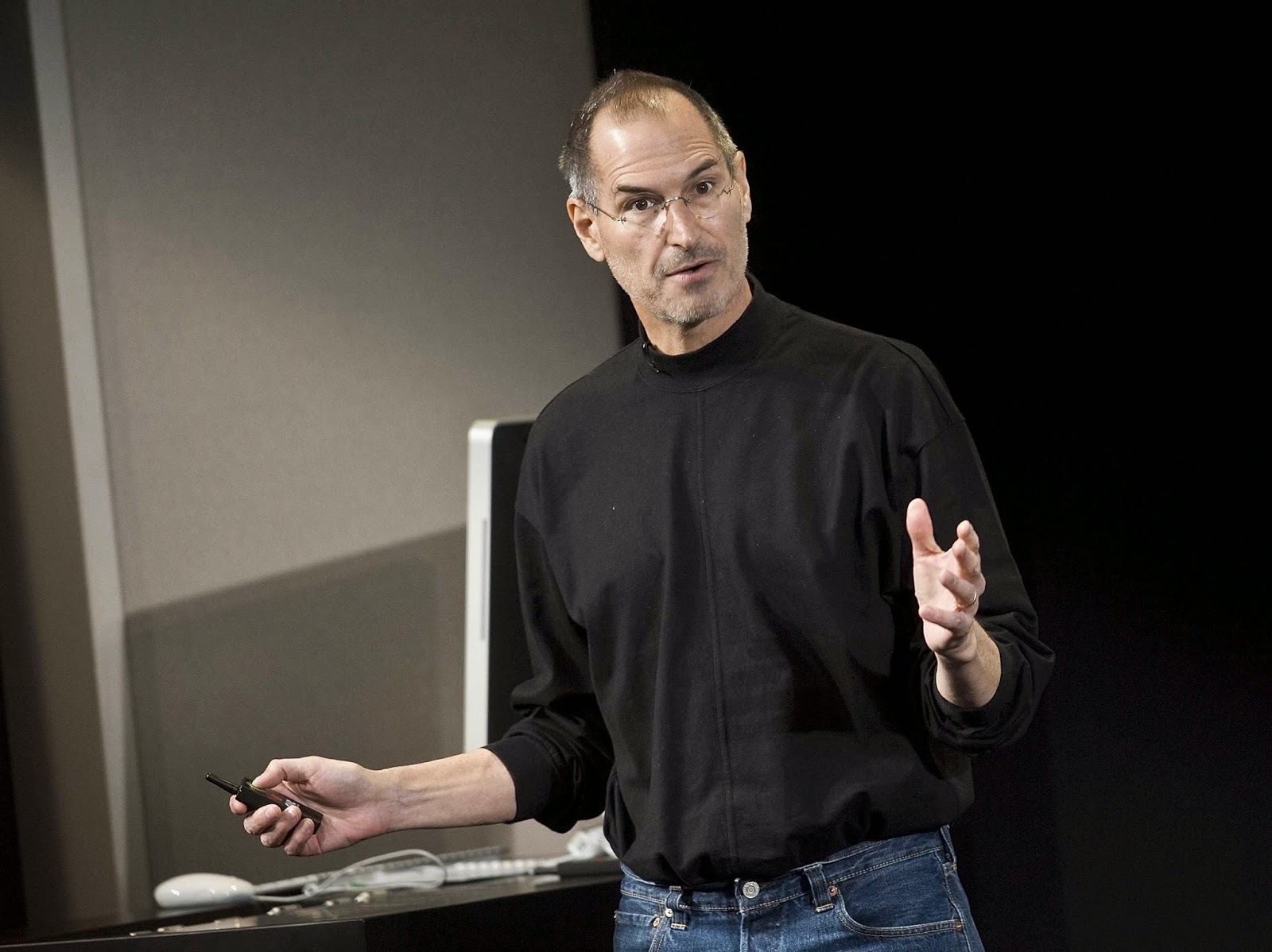

More than this, it is one man's vision, for Steve Jobs was Apple, and from the moment Jobs co-founded Apple on April 1, 1976, the vision was unwavering: to change the world.

Jobs set about changing the world one product at a time, beginning with the world's first mass-produced microcomputer, the Apple II, and then the first all-in-one computer, the Macintosh.

Jobs' inspirations around this time included religion and drugs. In 1974, he travelled to India in search of spiritual enlightenment, and came back a Buddhist, with his head shaved and wearing traditional Indian clothing. He also experimented with LSD, saying later, in an interview with the New York Times, that it "was one of the two or three most important things I've ever done in my life". Jobs had always said that people who do not share his countercultural roots can never fully relate to his thinking.

This thinking was responsible for a succession of zeitgeist-catching products – the iMac, iPod, iTunes, iPhone and iPad. Each is a masterpiece of design and function in perfect harmony, and each is imprinted with Apple's DNA, from components that few ever see, right down to product packaging. Each is imprinted with one's man's unrelenting, unforgiving obsession with perfection.

Unforgiving, because Jobs let nothing, nor nobody, stand between Apple and perfection. A cultural and business icon he may have been, a dream boss he certainly wasn't.

Moody and with a white-hot temper, tales of Jobs' personal abuses are legion. He parked his Mercedes in handicapped spaces on the Apple campus, reduced subordinates to tears, and summarily fired employees.

Author Robert Sutton was compelled to include Jobs in his bestselling 2007 book 'The No Asshole Rule' because "as soon as people heard I was writing a book on assholes, they'd start telling a Steve Jobs story".

But, as venture capitalist and former Apple executive Jean-Louis Gasse observes, "Democracies don't make great products. You need a competent tyrant."

If tyranny is a by-product of perfection as a brand value, then Apple's shareholders don't care a jot. Research firm Millward Brown Optimor (MBO) ranked Apple third in its 2010 Most Valuable Global Brands, behind Google and IBM, but ahead of Microsoft (again). MBO also estimated that year-on-year, Apple's brand value was up by 32% – the biggest increase of any of the 100 brands.

So, as Apple loses its dictator-cum-messiah? Will its brand suffer? The world may already know the answer to this, because Jobs and Apple have already parted company once.

Coup

In a 1985 boardroom coup, Jobs was forced out of his own firm by CEO John Sculley, whom Jobs himself had prised from Pepsi (with the words: "D'you wanna to sell sugared water for the rest of your life, or d'you wanna change the world?")

Jobs' big mistake was to forget Apple had shareholders. Sales of the first Macintosh computer in 1984 were catastrophically poor; while aesthetically wonderful, they were also underpowered, and no one had yet written any applications for them. Implored by Sculley to concentrate on the company's profitable Apple II line, Jobs refused, and the board sided with Sculley. Jobs was out.

"There was relief, as everyone had been terrorized by Jobs at some point," recalls Larry Tesler, a computer scientist at Apple for 17 years. "But we were worried what would happen to the company without its visionary and founder, and without his charisma."

"Apple never recovered from losing Steve," confirms Andy Hertzfeld, one of Apple's earliest employees. "He has a reality distortion field. In his presence, reality is malleable. He can convince anyone of practically anything, but it wears off when he's not around."

Without Jobs' maniacal striving for perfection, Apple drifted toward mediocrity, becoming a producer of beige boxes that, while popular with creatives, enthused few others.

Over time, and under a succession of CEOs, the Apple brand became almost homeopathically diluted. The low point came with the 'Mac clones' strategy of the mid-1990s, under which the company licensed its Mac OS operating system to third-party hardware vendors, who preceded to undercut Apple's own products, driving the company towards extinction.

And what of Jobs during this decade away from Apple? He kept pretty quiet, merely founding the Pixar animation studio in 1986, which he sold to Disney in 2006 for $7.4 billion, making him Disney's largest shareholder.

Jobs also started another technology company, NeXT, which sold super high-end computers to scientific and academic markets. It was to be his ticket back into Apple, after the company bought NeXT for $429 million in 1996.

Pefection

At that time, 'Apple' and 'beleaguered' rarely failed to appear in the same sentence, but this was before Jobs began injecting perfection back into the Apple brand.

The company's epic climb toward supremacy began when Jobs recognised that, in his enforced absence, a design genius had joined the Apple ranks. London-born industrial designer Jonathan Ive was duly tasked by Jobs with designing a computer that could change the world all over again. His creation was 1998's iconic transparent blue iMac. Within months, every electronic product – from irons to vibrators – were being designed using translucent blue plastic. Apple was back, because Jobs was back.

Everything, and yet nothing, had changed. In Jobs' mind, the Apple brand has always been about design perfection – whether it's software or hardware.

As far back as 1982, he was actively encouraging his designers to think of themselves as artists. Back then, he took his Mac design team on a field trip to a Louis Comfort Tiffany exhibition, because Tiffany was an artist who was able to mass-produce his art – just as Jobs wanted to do.

He even insisted that his design team sign the interior of the Macintosh case, like artists signing their work. "He encouraged each one of us to feel personally responsible for the quality of the product," Hertzfeld says.

The way Apple people work has not changed either. They turn in long hours with a passionate, almost messianic fervour, driven by the fear-tinged respect that Steve Jobs inspired.

Under Jobs' guidance, Ive and his team have gone on to give us the iPod, iPhone and iPad. Perfection as a brand value requires ultimate control, which in turn requires the ultimate control freak.

As Jobs departs for this final time, he will be comforted to know that excellence has been institutionally ingrained in Apple's products, and that only mismanagement on a cataclysmically dire scale can shake the Apple brand free of the quality that people have come to associate with it.

Source: macworld.co.uk